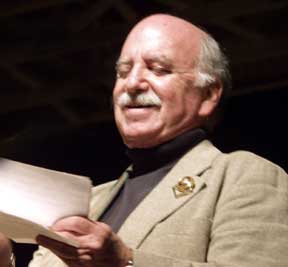

Gene at the 40th Philadelphia Folk Festival, Aug. 2001

|

|

Gene at the 40th Philadelphia

Folk Festival, Aug. 2001

[For those of you just tuning in: last time we were discussing the range of activities Gene Shay was involved in, as of 1978, when the interview took place, from MC’ing the annual Philadelphia Folk Festival – which of course he still does, as the festival enters its 45th year, in 2006 -- to hosting his famous radio interview-and-music show, "Folk Music With Gene Shay" – now on WXPN, the University of Pennsylvania’s NPR outlet. At this point in the conversation, we’d been discussing some of those early interview subjects, and the non-availability of tapes from those 60’s and 70’s "folk revival" shows.]

John: I know there’s a book out about Richard Farina, by Neal and Sally Hellman. But I don’t think it’s that kind of book.

Gene: No, I guess it’s a songbook, really. And I’ve been asked by a number of magazines, publications, to do record criticism. That’s something that for some reason or other I always push off to the last. I don’t know, I’m not quite sure why. I guess it’s because I have to force myself to sit down and write headlines, or brochures for rent-a-car agencies, things that don’t particularly thrill me. I guess I’d rather just enjoy music, listen to it, play it on the radio – things that I enjoy, rather than, ah, start to analyze, pontificate on it, what I think is right or wrong with this particular album. I can talk about it, yeah, but I haven’t gotten into any of that yet.

John: It’s a difficult task, I think, to do record reviews. You can’t please everybody. Do we have some time here yet?

Gene: Oh, sure.

John: Here’s a question – a media question, you might say. What’s the difference you see between live, onstage MC’ing, or a radio show, or perhaps doing TV? What media distinctions do you see?

Gene: Well, one of the joys of being onstage is that you get immediate reinforcement. You know at once what that response is. On the radio you’re never sure. You can’t be out there, you can’t know how they’re responding, you know, "Who does he think he is," or "He’s got his facts all wrong." You know. Whereas if I say at the Folk Festival, you know, "Here’s Doc Watson and his lovely wife Merle" – you know what I mean – it’s a variation on the old Gershwin joke – and right away I get either a boo or a laugh or a correction. But I could say on-air, "Here’s a piece that was recorded in the thirties," and five or six days later get a response saying, "It was recorded in 1929." I think that I work better in front of live audiences, though of course I can’t play any records for them. I can sit in – I regard my radio program as an extension of my living-room, with a bunch of friends, as sort of my audience. The people who like my program, I sort of feel as if I’m on the same wave-length with them. We like the same kind of music, their interests are catholic enough that they can appreciate a lot of different kinds of music. I consider my audience my friends. That’s why I can mix it up for them—I try not to be too bluegrassy, though I do play bluegrass. I try not to be too British Isles-y – though just like everyone else I’m human and have a tendency to go off the deep end occasionally. So I have to keep thinking about that. I don’t know if I really have any preference. I know I do love radio. I’ve always been fascinated by broadcasting, by communications, by electronics—not so much the technical end of it, just what you can do with your voice and sound effects. Like those seagulls at the beginning of the National Geographic Society record of sea-shanties from that album with Lou Killen and John Roberts and Tony Barrand. The same effect that was used by Procol Harum in "Salty Dog"? I think the thing I’m interested in is communicating, I don’t care what the medium is.

| John:

I wonder if you find yourself more at the mercy of a producer or director

in a control room - you know, the chap who can focus one of the cameras

on something that you didn’t care about, or didn’t focus on something

that you really wanted close up? Gene: Well, I’ve never been in that situation, I’ve never done my own program on television. But if I were to do my own program, I would think that I would want it to be as loose, as informal – maybe a bit more structured – as my radio show. But certainly my producer there would have to be a friend, or someone I had faith in, one who understood, who had sensitivity for the kind of thing I did. You know, I’m not a Mike Douglas, I’m not a Tom Snyder, that kind of thing. John: I was thinking of something else. I know the Seattle Folklore Society is advertising the fact that they have videotapes of musicians, especially focussed on their techniques. Gene: Radio? John: No, from TV programs. People like Reverend Gary Davis, Libba Cotton. It seems – I’m not sure of this – that they had appeared in the Seattle area, and were taped for television, and the producer focussed on the instrumental techniques and so forth. It does sound as if it would be a very useful teaching device. |

|

Gene: That’s interesting. I didn’t know those tapes existed.

John: It’s John Ullman, of the Seattle Folklore Society, who runs the Traditional Arts Booking Service, who has produced this.

Gene: Well, I’ve just produced a tape with Lew London, the Lew London Trio, and I’m contemplating doing a series of performers, preferably acoustic, so we don’t have too many audio variations, electronic problems.

John: Of course, putting Lew London on videotape is not going to help too many people.

People will see it, but they still won’t believe it! [Laughter] They’ll see those fingers blurring, and they’ll still say, "No! Can’t be done!"

Gene: Same thing with a Doc Watson. H’m. But I think it would be nice to tape a lot of performers, especially traditional performers who’re not going to be with us too long. It’s nice to know there is a videotape of the Rev. Gary. I mean, we have records of his, but I didn’t know there was also videotape. And Elizabeth Cotten? It’s just like, one of the stations is documenting Ola Belle Reed and her family. And that’s really important. It really should be a part of the American archives.

John: And of course Ola has her own museum at home, and she is interested in making sure that it is kept on.

Gene: I would love to do a TV series, produce it, on people like JP Fraley and AL Lloyd – I’d love to go to England with a crew, and just get him to sing some songs, tape it, you know? There’s just so many things I would like to do. But that requires funding and so on.

John: I did have some other questions, though most of them have been answered, though not necessarily in the sequence I had in mind. But there was one – what do you see as the future for – I call them "folk music halls," the term "coffeehouses" has such poor connotations for me – do you think there’s much chance for many new people breaking into and running such an enterprise, or do you think it’s overcrowded?

Gene: I think there is still plenty of potential. There are a lot of colleges and community people who are sponsoring coffeehouses. Mostly on a non-profit basis. That encourages young guitarists to perform in front of an audience. It also stimulates an interest in the source of the music. I think that any sensitive person who picks up the guitar and starts to learn a couple of ballads, chances are they’ll start to do a little investigating, and learn about some of the variants, and will start to learn what the "folk process" is all about, tracing back to the ballads too. I think – and I hope – maybe it’s wishful thinking – but well, sales of guitars are as strong or stronger than they’ve ever been.

John: That’s one good sign, isn’t it?

Gene: Sure. I hear about other coffeehouses opening up. In West Chester, The Carriage House is a recent addition, at Widener College. There are more colleges out of the immediate area – The Main Point is, you know – Tom Rush and I helped put together that benefit concert, they’ve changed their status to non-profit, and fortunately they’re OK, still in business – they’re not "thriving," but they are still in business. And I think there is room for it. It does give people a chance to get up on stage, and there are a lot of other people out there, with guitars, living-room singers, who sing for their friends and family, and who are very good – and they have no platform, they can’t get up on a big stage like The Main Point – they have no track record, no recording contract or a name. So it gives them a chance, an opportunity. Maybe it’s a church coffeehouse, in a basement somewhere.

John: I know I heard a rumor recently that someone in this town is trying to open up a place which would have a liquor license, and also have this kind of acoustic music.

Gene: I’d like to see that kind of place open up, and flourish.

John: I know that up in New York, Albany, there’s "Reactionary Mary’s."

Gene: Oh, there are quite a few of them in operation. There are places that serve liquor, and have folk music, and they’re very successful. I don’t see why they wouldn’t be successful here too. But I can understand The Main Point’s reluctance to even try to get a liquor license, because the people who own The Main Pint do specifically feel that young people – there are a lot of them in their particular area – deserve a place where they can see someone like a Tom Paxton, a Tom Rush, The Newgrass Revival, John Hartford, Sparky Rucker, whoever. And there’s the Cherry Tree Folk Club – there’s a lot of folk club activity in this area. And WXPN, and now WUHY – Greg Giamo, one of my former assistants, is doing radio programs now. And there’s another by Tor Johansen, and Bob Carlin, of the Delaware Water Gap String Band. I wish I knew them all, there’s lots of them. And there is the network, Public Broadcasting, what would we do without that? I mean, talking of taking ‘XPN off the air – that would be like cutting off a major source of folk music!

John: Speaking of folk-pub places – there’s the Eagle Tavern in New York City, and it has a liquor license, sells its beer and so on, but it has its music in the back room. And I believe it’s Mick Moloney who says the atmosphere there is very like an English folk pub, where they have their beer in front of them, but they keep the noise down, and they really listen to the music.

Gene: That’s great! Look, for many years the place where Dylan got his start, Gerde’s Folk City – Phil Ochs, and I remember the time I was managing Billy Vanaver here in Philadelphia, and booking them, and they’re drinking places, you’d see Van Ronk in there, Patrick Sky – oh, and there’s Billy Vanaver, on the cover of The Folk Life!

John: Well, since you mentioned him….

Gene. An old Philadelphian. Well, I don’t see any reason why a drinking club couldn’t be a folk club. There’s certainly an adult audience that would rather not go to The Main Point because they really don’t want coffee and a cheese-board. They want – much as they would like to hear bluegrass – they would rather – well, a good example is the Bryn Mawr Beef and Ale House! For a while there they had JD Crowe and his group [The New South].

John: Well, I saw New Appalachia there. Now, that’s another young, local group that plays solid bluegrass.

Gene: I don’t know them. They should send me a tape.

John: That’s a thought. Going back to the coffeehouses question – I guess I thought the commercial problem was that if you cut yourself off from liquor sales, from that adult audience, to keep a coffeehouse going with just coffee and pastry –

Gene: Well, then you have to ask, "Who’s on stage?" You just cannot make as much money in a coffeehouse on the food as you can on a bar. There’s a tremendous profit potential when you have a liquor license. And that is why a lot of the folk clubs are always in trouble…. The performers, after appearing at the club a few times, their prices rise, as they become more popular, and after a while they’d rather do college concerts and in one night make as much money as they could make in three nights in a coffeehouse – where they’d also have to do two shows a night. So, if you have the real choice – well, if you’re a Michael Cooney and you love to sing anywhere and everywhere – or a Steve Wade, with all the enthusiasm –

John: -- and that energy!

Gene: It’s a very different thing. But even they would prefer to do concerts. But you’ve got to build that audience, to be able to fill a concert hall. And the only way to do that is to start on it may be a coffeehouse level, and first, and then on. But you get people who play The Main Point – like Tom Rush – who also do play The Bijou – which is a drinking club – and who also do college concerts. And are successful at all three. And I think it just goes to prove the strength of the performer, and how compelling a performer is, and how well-liked and popular. And of course the profit angle, when it comes to coffeehouses versus drinking places, like John and Peter’s in New Hope, well, they have a very good concept, where they give the gate to the performer. And the John Herald Band is one of the best contemporary bluegrass bands, I think – John is certainly one of the best singers in the business, and also an excellent songwriter, they can do very well there on a weekend. They can make almost double the money they can make at The Main Point, or double or triple in one or two nights there. And that’s just because it’s a drinking club, and the owners of the club can afford to give the higher cover charge to the performers, as they make enough profit on the beer and liquor sold, whereas The Main Point can’t afford to do that. The Main Point would have to charge much larger admission prices, which would turn away a lot of the people. They know that, so they’re very reluctant to try it.

John: It does seem as if they’re caught right in the middle.

Gene: Oh, yeah, it’s tough for them.

John: A different question I had. I had mentioned in The Folk Life some months ago that you were willing to give space to young performers on your radio program. Is that kind of option still available, and how would the performer get in touch with you?

Gene: All the time. All I ask is that they send me a tape, and that I can tell, you know, that they’re not terrible. I mean, I’ve had people that I’ve been embarrassed to have on! Either because I didn’t listen enough to their tape, or what was on their tape wasn’t representative of what they were doing. I was actually embarrassed, because I’d like to introduce people to the Philadelphia audience on my program, people with potential, diamonds in the rough, so to speak. I’d put almost anyone on – I shouldn’t say that! –but if there’s a sparkle of talent in there, I like to do it. Because it’s an experience for them to be heard, and when and if they become better-known, they’ll remember when they come to town, and they’ll still be willing to come on. In a way, it’s a trade deal, if you want to call it that. I’m giving them exposure and the audience is getting entertainment, and we’re all getting experience from it. It’s a little bit of an adventure to discover – and I discover right along with the audience, we discover new talent, new songs, old songs that somebody had just revived. I mean, to hear Kevin Roth at the concert we just did at Widener, he did a song I’ve always loved, "Kitty Alone," and I always heard that from

Martha Beers, the song as I first heard it was from an album of the Beers Family, a lovely melody, and I always thought, "Wow, what a lovely melody, what a beautiful thing, isn’t it a shame there are no contemporary singers using that melody, doing something with it," and here is Kevin Roth, a young, talented guy, with a great singing voice – just great – so when I heard that, I said, "Wow!" to myself – "Somebody grab that!" I walk around with melodies in my head that I like, and I wonder why somebody doesn’t get hold of it, even if they change it a little bit, in the commercial sense. Like "The Twa Corbies," which has a nice, driving, minor key thing, a fine feeling.

John: Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger do have a lovely recording of that in the Long Harvest series.

Gene: Oh, Steeleye Span have also recorded it. There are some really fine recordings of it. I have one by a fine Scottish singer called Alistair MacDonald, and I’ve been trying to track the guy down. He has an album, Tam Lin, and I got it from a doctor friend of mine from Philadelphia, who got it over there. And he wrote him, tried to contact him, to ask for more albums, telling him I played them here, and never got an answer.

John: Well, here’s my last question, Gene, if you don’t mind. You’ve given me a lot of your time today, and I really appreciate it. OK. Is there such a thing as music you listen to at home for pure pleasure? I know there is so much you have to listen to just for business reasons like "keeping up."

Gene: I go in cycles. Oh, occasionally I’ll pick up on something that is very "au courant," if that’s the right phrase. Something that’s very popular at the moment.

Like when Abbey Road first came out. Or when the Joe Cocker albums first came out. But at the same time I’m still listening to new releases by the Putnam String County Band, or Harry Tufts’ new album, Grubstakes.

John: Is that on Folk Legacy?

Gene: No, it’s on a small label called Biscuit City.

John: Oh, right – out of Denver, Colorado.

Gene: They do some good sea shanties on there, they do some other things. Harry does a beautiful version of "Buffalo Skinners," and so on. And lately I’ve been very taken by Mary McCaslin – and have been for I’d say the last six months to a year. I’ve always liked her singing style, the way she treats songs – even Beatles songs. She just did "Pinball Wizard," with a banjo. She’s very reminiscent of Hedy West. And Jim Ringer is another of my favorites. I like Lew London – I’m especially taken with his guitar and voice in performance. I listen to Bruce Springsteen, because I think he’s incredible. I like some of the new Joan Baez stuff. I listen to Bob Dylan. And I always go back to my old albums. Lately I find myself listening to jazz. My old Miles Davis albums. John Coltrane. Jimmy Yancy’s piano. Thelonius Monk. Sometimes I listen to Dave Brubeck with Paul Desmond, doing "Take Five," or "Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me," or "Balcony Rock…."

John: "Blue Rondo A La Turk"?

Gene: Yes – exactly. A lot of those songs have certain connotations that go along with them – they remind me of certain times in my life, certain people in my life. It’s a recall of experience, so the song has a double meaning for me. I always liked it as a song, and then it reminds me of a nice thing. That’s when I’m feeling nostalgic. And then when I’m feeling adventurous? Two nights ago I just heard a Brazilian jazz musician who’s been around for years, and I’d never heard of. Guy with a beard, and a full head of white hair, like Albert Einstein. Heavy-set. A strange name I can’t pronounce. Incredible jazz piano that was syncopated in a way I’ve never heard. I’m going to try to get that album. I don’t know what it’s called, I don’t even know his name. But I’ll tell you, there is one kind of music I like especially, Peruvian music, the kind of thing Los Cunjo Males used to do. I’d like to hear more of that music. I know David Lewis did some recordings on Nonesuch, field recordings, actually. Nut-charangas and wooden, globular flutes, that high, Andean kind of sound – it’s just a thing I find especially appetizing. I just wish there was more of that…. There are a couple of Chilean groups, but I’ve only heard a very little bit. There’s one, I have their album, a lot of which is of a very protest nature –

John: Rightly so?

Gene: Deservedly so! But there are other parts which are, I think, closer to Peruvian mountain music.

John: I keep remembering what Phil Ochs said about that. "In a time of ugliness, beauty is its own protest."

Gene: H’m. Ah, well…. Phil Ochs was… I was…. That was another tragedy that came close to home. Because Phil Ochs was a good friend.

John: I read that Bob Gibson said one of the things behind that was, after Phil got mugged in South Africa, he lost a couple of the high notes off the top of his range, and couldn’t sing his own songs any more.

Gene: Oh, yes. He was very down about that. I remember he had dinner at my house, right after seeing a specialist. He’d seen two specialists, one who told him that he would regain his vocal range, and then he got a contradictory prognosis from another doctor. He didn’t know which way to go. It was one of the worst times I’d ever seen him. He had a terrible habit of this, of scratching his chest, you know, a nervous tic. I asked him about it, and he said, "No, it’s just nervousness." I thought he had a rash or something, putting his hand in his shirt. You know, it was a bad time for him. And I think it was shortly after that time when he started drinking and acting silly up in New York. Then he straightened up! Everyone thought he was going to be all right….

|

John:

Ach, well. Look, I’ve been enjoying this talk, Gene, but I know you’re

a busy man. Gene: Oh, right. I’m supposed to be somewhere else right now, about five blocks from here. Saul Broudy’s going to be here soon… John: Thank you very much for your time, Gene. Gene: Well, I hope you can make some sense out of it! John: Oh, I think we can reproduce it as near intact as possible. Gene: All right. You know, the fact of my longevity on the air in Philadelphia has a strange kind of advantage, when I have young people listening to me whose parents listened to me…! I remember one time Benjy Aronoff introduced me to an audience as. "Here’s the guy who taught us all about folk music." And I thought, "He didn’t mean ‘teach,’ but played the records and the artists that turned people on to things." And what that comes down to is still an extension of me in my living-room with my friends and my records. If you ever do come over to my house, John, I guarantee you I’m going to play some records for you! [Laughter] Just strap you in a chair…! I mean, when I find something like "Sheebeg and Sheemore," or Carolan’s stuff – I just say, "Gimme more of this music! |

John: Speaking of Benjy Aronoff reminded me – David Amram‘s coming round again soon –

Gene: I know! I’ve heard a tape of David’s new album, which is very un-folky, except that the tunings are all kind of modal, as if he’s getting back into the jazz and combining it with salsa, taking the colorations of traditional music, themes from Spain, from Puerto Rico, or wherever, Latino themes, drums, like Miles Davis would.

John: That’s a Ray Mantilla influence, probably.

Gene: Also the trip to Cuba too. There’s a lot of interchange there.

John: Well, that’s David.

Gene: I don’t know if you’re familiar with Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain?

John: Not at all.

Gene: A beautiful album – still available. The thing – the arrangements are linear, but you can separate out the lines, the horn and so on, and they’re all pretty melodies, but taken together…..

John: The man hears music in strange ways, doesn’t he? H’m. Sketches of Spain?

Gene: An old Columbia album. There are a couple of traditional songs in there. The arrangements are by Gil Evans, who’s my favorite jazz arranger of all time…. Anyway!

John: Thanks again, Gene.

Gene: My pleasure. I hope you can sort it out.

[Not that I especially care to try to try to untangle such a fine web of allusion and suggestion, a network of feelings and thinking. I’d rather just enjoy, wouldn’t you?

And remember – "Folk Music with Gene Shay," Sunday nights on WXPN, 90.1 FM, the University of Pennsylvania’s NPR outlet. If we don’t see you in the crowd at the Philadelphia Folk Festival, enjoying Gene Shay’s audience-fed "Bad Joke Marathon."

And keep listening to that 4-CD boxed set of music from 40 years of the Philadelphia Folk Festival, on Sliced Bread Records…]